The Lung Microbiome and Dysbiosis

The “microbiome” is a hot topic in respiratory medicine, with researchers from diverse fields such as chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, bronchiectasis, pulmonary fibrosis, and lung transplantation seeking to use the newly accessible technology of bacterial ribosomal RNA sequencing and related technologies to characterize airway bacterial communities and to determine the extent to which “dysbiosis” may contribute to the pathophysiology of lung disease.

From the article “Microbial Dysbiosis after Lung Transplantation” in the Nov 15, 2016 ATS Journal

Researchers are looking at how shifts in the bacterial communities in people’s airways might contribute to their lung disease and its progression.

What is the Human Microbiota? The human microbiota consists of the microbial colonies found on or in the body. Ideally, they are benign and actually beneficial. A balanced microbiota has colonies that compete with each other for space and resources. In the digestive tract, they help with digestion. On the skin, in the lungs, and elsewhere, they help protect the body from penetration or overgrowth of dangerous microbes.

What is Dysbiosis? It is an imbalance in bacterial colonies in the body. The author, James D. Chalmers, M.D., Ph.D. of the article above, describes three ways for dysbiosis to occur in the lungs.

Invader: A new organism enters the airways and disrupts the existing communities by outcompeting other bacteria for resources, resulting in a loss of diversity.

Outgrowth: An outside factor such as antibiotic use or a viral infection allows one organism already existing in the community to outperform others and become dominant.

Immune Selection: An inflammatory event, which activates the immune system, causes an attack on organisms in the community, killing susceptible ones and leaving tolerant/resistant ones.

The author notes that there are likely other models for the creation of dysbiosis, and these can be more complex and can occur simultaneously.

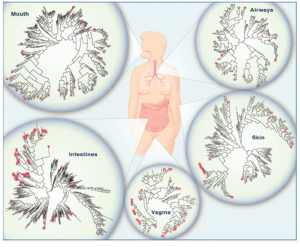

The image below comes from the National Academy of Sciences, The Social Biology of Microbial Communities: Workshop Summary (2012) and it shows bacterial species diversity in various areas of the body.

For more about microbiomes and lung disease, see these articles from the References section of the ATS Journal article above:

Wang Z, Bafadhel M, Haldar K, Spivak A, Mayhew D, Miller BE, Tal-Singer R, Johnston SL, Ramsheh MY, Barer MR, et al. Lung microbiome dynamics in COPD exacerbations. Eur Respir J 2016;47:1082–1092. Medline

Smith DJ, Badrick AC, Zakrzewski M, Krause L, Bell SC, Anderson GJ, Reid DW. Pyrosequencing reveals transient cystic fibrosis lung microbiome changes with intravenous antibiotics. Eur Respir J 2014;44:922–930. Medline

Han MK, Zhou Y, Murray S, Tayob N, Noth I, Lama VN, Moore BB, White ES, Flaherty KR, Huffnagle GB, et al.; COMET Investigators. Lung microbiome and disease progression in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis: an analysis of the COMET study. Lancet Respir Med 2014;2:548–556. CrossRef, Medline

Dickson RP, Erb-Downward JR, Freeman CM, Walker N, Scales BS, Beck JM, Martinez FJ, Curtis JL, Lama VN, Huffnagle GB. Changes in the lung microbiome following lung transplantation include the emergence of two distinct Pseudomonas species with distinct clinical associations. Plos One 2014;9:e97214. CrossRef, Medline

Charlson ES, Diamond JM, Bittinger K, Fitzgerald AS, Yadav A, Haas AR, Bushman FD, Collman RG. Lung-enriched organisms and aberrant bacterial and fungal respiratory microbiota after lung transplant. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2012;186:536–545. Abstract, Medline